Supporters of the “price negotiation” process established in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) claimed that it would not harm generic or biosimilar competition. They explained that the IRA’s price negotiations would take effect only when a generic or biosimilar version of a drug is not available. However, they neglected to share, or failed to realize, that the law set up a process under which a drug would have price controls applied before a generic or biosimilar even had the chance to come to market. Two recent events drive this home and reveal that IRA price controls serve only to undermine lower-priced generics and biosimilars.

IRA Price Controls are Targeting Brands for which Generic or Biosimilar Competition is Imminent

One of the last acts of the outgoing Biden Administration was to announce the selection of the next 15 drugs for price negotiation. Although framed as the next step in reducing costs for patients, the fact is that the vast majority (13 of the 15) have generic competitors already approved or seeking approval by FDA.1

Selected Drug | Approved ANDAs | Tentatively Approved ANDAs | Pending ANDAs |

Semaglutide | 0 | 0 | 12 |

Enzalutamide | 3 | 5 | 5 |

Pomalidomide | 6 | 1 | 3 |

Palbociclib | 1 | 13 | 5 |

Nintedanib | 0 | 4 | 1 |

Linaclotide | 2 | 1 | 4 |

Acalabrutinib | 0 | 2 | 5 |

Deutetrabenazine | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Linagliptin | 3 | 11 | 1 |

Rifaximin | 0 | 4 | 5 |

Cariprazine | 2 | 1 | 0 |

Sitagliptin-Metformin | 0 | 13 | 17 |

Apremilast | 11 | 5 | 4 |

Total | 29 | 60 | 63 |

Grand Total = 152 |

This highlights the fundamental flaw in the timing of the drug negotiation program. Although the law’s authors exempted products from negotiation when a generic or biosimilar was approved and marketed, the law explicitly starts the negotiation process before generic and biosimilar competition ever has a chance to begin.

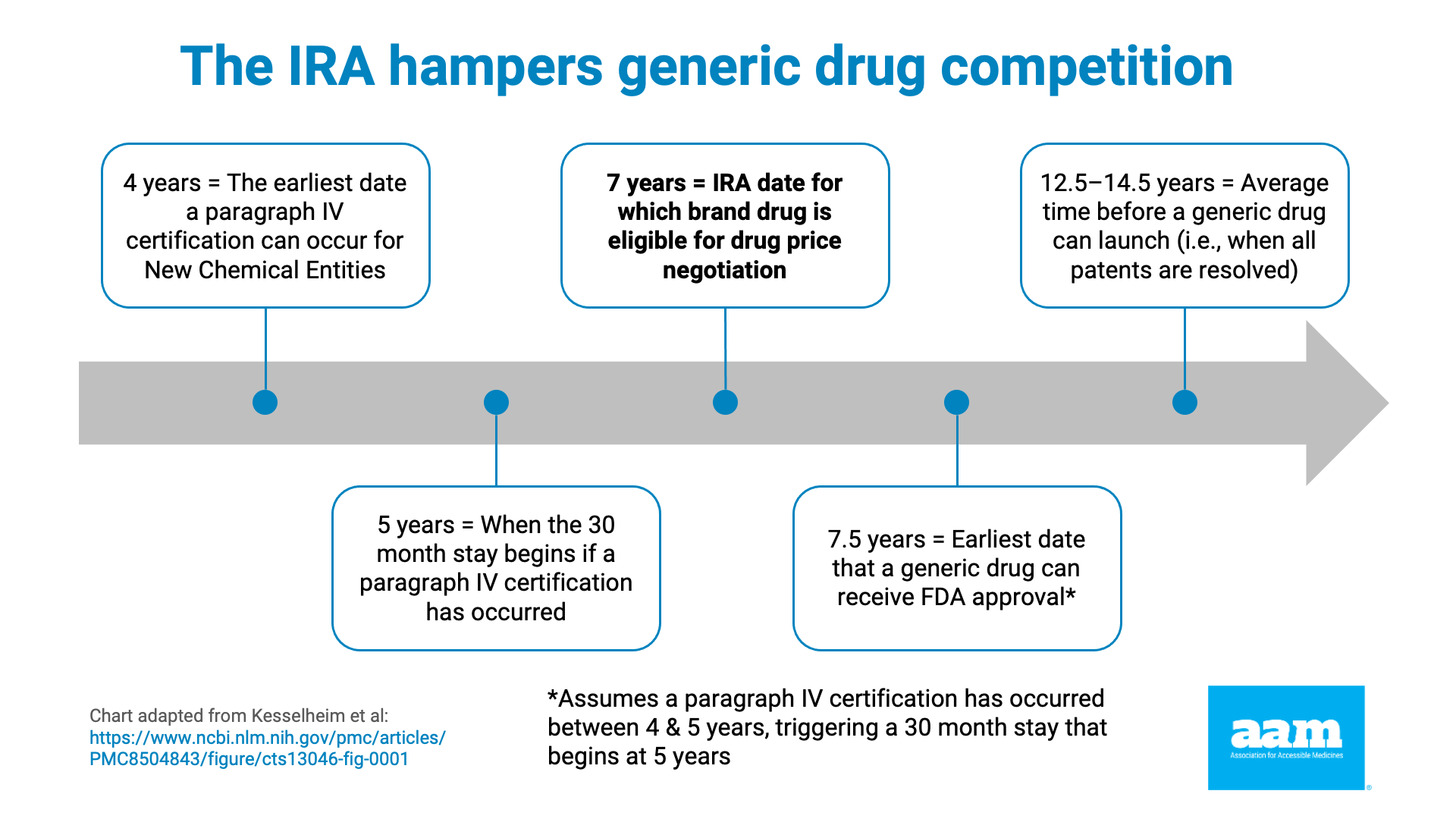

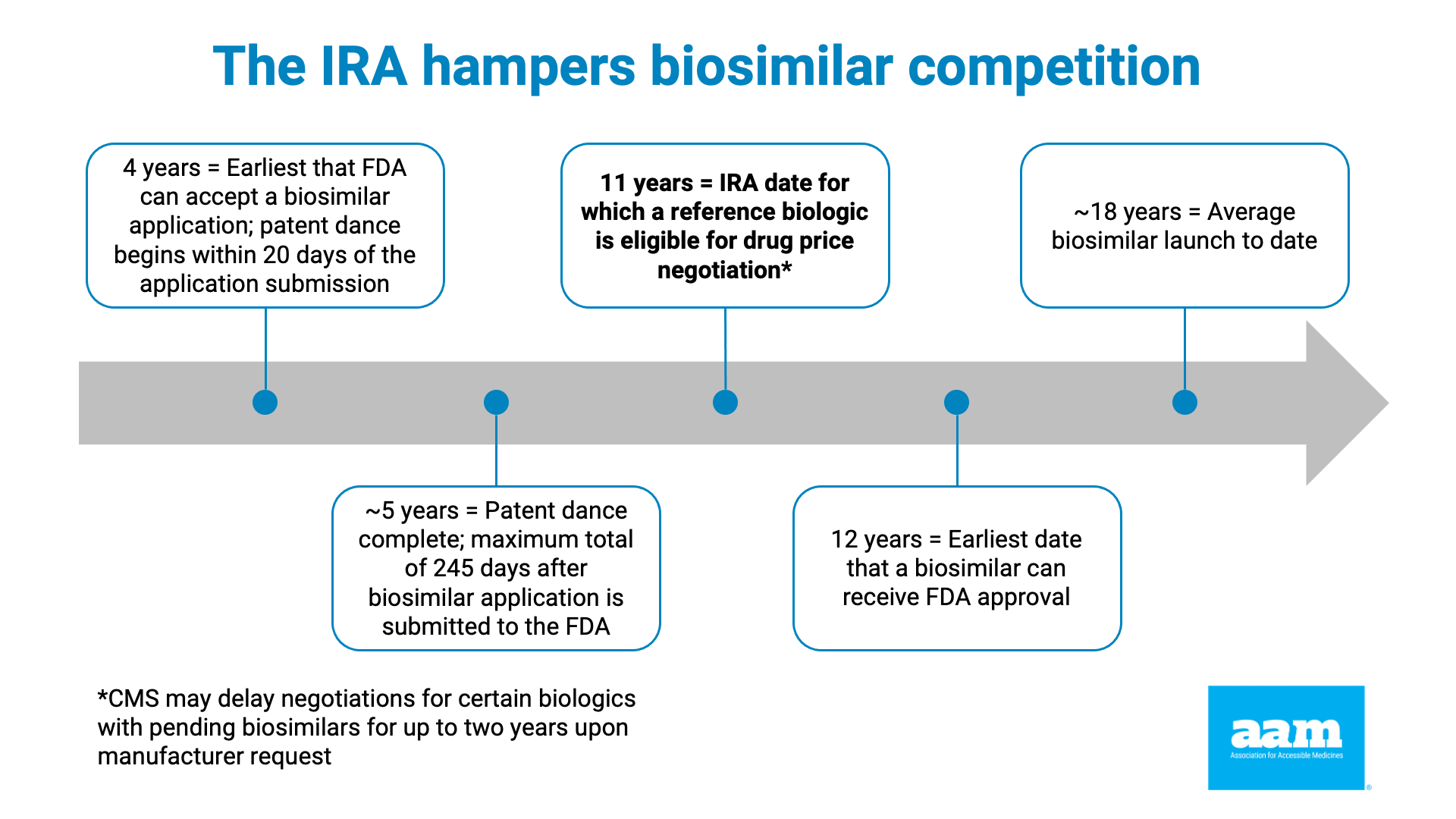

The IRA does this by instituting the price control process when the brand drug has been approved for 7 years (or, if a biologic, it was licensed at least 11 years ago). As noted in Exhibit 1 and 2, as well as the chart below, data showing that the average market entry of a first generic is between 12 and 14 years, and a little over 18 years for a first biosimilar (the earliest a biosimilar has ever entered is just over 13 years), makes clear that preempting lower-cost competition through price controls is a feature, not a bug, of the IRA.

Reference Product | Date of approval for reference product | First biosimilar | Date of launch of first biosimilar | Number of years and months between reference product approval and first biosimilar launch |

Actemra® | Jan-10 | Tyenne® | Jul-24 | 14 years, 6 months |

Avastin® | Feb-04 | Mvasi® | Sep-17 | 13 years, 7 months |

Epogen® | Jun-89 | Retacrit® | Nov-18 | 29 years, 5 months |

Eylea® | Nov-11 | Pavblu® | Oct-24 | 12 years, 11 months |

Herceptin® | Sep-98 | Kanjiti® | Jul-19 | 20 years, 10 months |

Humira® | Dec-02 | Amjevita® | Jan-23 | 20 years, 1 month |

Lantis® | Apr-00 | Semglee® | Nov-21 | 21 years, 7 months |

Lucentis® | Jun-06 | Byooviz® | Jun-22 | 16 years |

Neulasta® | Jan-02 | Fulphila® | Jul-18 | 16 years, 6 months |

Neupogen® | Apr-98 | Zarxio® | Sep-15 | 17 years, 5 months |

Remicade® | Aug-98 | Inflectra® | Nov-16 | 18 years, 3 months |

Rituxan® | Nov-97 | Truxima® | Nov-19 | 20 years |

Stelara® | Sep-09 | Wezlana® | Jan-25 | 15 years, 4 months |

Tysabri® | Nov-04 | Tyruko® | Jan-24 | 19 years, 2 months |

Average: ~ 18 years |

The impact of generic and biosimilar competition is clear. According to the FDA,3 the presence of 4 generics on the market creates price reductions of 60 percent or more, and 6 generics can result in price reductions of 95 percent or more. Further, biosimilars are not only bringing lower prices, but they are also driving down brand prices. But this robust competition and downward pressure, which can be delayed by brand manufacturer abuse of the patent system including through patent thickets, is at risk due to the unpredictability of IRA price setting.

The IRA Price Controls Actively Undermine Current Generic and Biosimilar Competition

This brings us to the second event. The outgoing Biden Administration also released a draft guidance on the implementation of the price controls in the Medicare drug program. Among the issues that they addressed was how Medicare plans are required to cover brand drugs with price controls and some exceptions to the rule.

Normally, Medicare drug plans choose to cover a drug that has the lowest net cost, whether a brand, generic or biosimilar. But the IRA states that while a price control is in effect for the brand, the brand will be guaranteed formulary coverage (even if a biosimilar or generic is on the market with a lower cost). But there is one exception to this – under the law, and laid out in CMS’ Draft CY2025 Part D Redesign Program Instructions, Congress put into place specific instructions about when and how a drug subject to a maximum fair price (MFP) could be substituted as part of a Part D formulary.

CMS summarizes it as permitting “a plan to immediately remove a brand name drug from its formulary or change the preferred or tiered cost-sharing status of the brand name drug if a newly available, therapeutically equivalent generic drug was added to the formulary at the same time.” In other words, a plan must cover the price-controlled brand instead of lower-cost generics or biosimilars but could choose to cover a later available generic or biosimilar even though this punishes a generic or biosimilar that launched earlier.

This is not merely a theoretical concern. Consider a specific example – Stelara® (ustekinumab), one of the drugs selected in 2024 for negotiation. (Stelara®’s MFP was published in August 2024, and it, along with guaranteed formulary coverage, will take effect for the 2026 Medicare plan year.)

- One biosimilar (Wezlana®) launched in January 2025 and at least five other biosimilar products are expected to launch in the first half of 2025 – Imuldosa®, Otulfi®, Pyzchiva®, Selarsdi®, and Yesintek®.

- Under the CMS approach as directed by the IRA, Medicare drug plan sponsors could cover those biosimilars at parity or in a non-preferred position but would still be required to cover the brand Stelara regardless of whether those biosimilars already on the market cost less than the MFP established by CMS.

- But if an interchangeable biosimilar were to come to market after Part D plans determine their 2026 formularies, CMS, under the IRA, would permit plan sponsors to immediately substitute the new biosimilar and remove coverage of Stelara® entirely, with the least amount of waiting time or administrative burden.4

- Given that Part D plans often submit their proposed formularies in June of each year, this could create a perverse incentive for manufacturers to delay market availability of a lower cost generic or biosimilar to maximize the potential market share available to a product eligible for immediate substitution.

IRA Price Controls Undermine Patient Access to Future Savings

To recap: IRA price controls are targeting products for which generic and biosimilar competition is often imminent, while directly undercutting generics and biosimilars that are already on the market (even at a lower price).

This not only harms generic and biosimilar manufacturers, but it makes it more difficult for manufacturers to justify that investment needed to bring a generic or biosimilar to market. While there will hopefully continue to be generics and biosimilars, it is likely that there may be fewer, and they may be slower to market. A recent analysis by the IQVIA Institute suggests that this slowdown is already underway.

The result then is less generic or biosimilar competition and slower generic or biosimilar competition. This translates into higher costs for a longer time for patients and taxpayers (and especially for employers who will not even have access to the Medicare price controls).

Because the negotiated prices only apply to the Medicare market segment, reference product manufacturers may actually be better off with government negotiated prices than by competing with generics and biosimilars in the open market. As a result of the uncertainty created by unpredictable price controls that take effect immediately prior to generic and biosimilar launch, manufacturers of lower-cost products may be discouraged from investing in the development of a generic or biosimilar, meaning that brand manufacturers not only get to retain more profits, but they also keep their monopoly for longer.

While supporters claimed the IRA would not harm generic or biosimilar competition, it is evident that this is not, and will not be, the case until reasonable changes are made to the IRA. Without significant reforms, patient access to lower-priced generics and biosimilars will be undermined, keeping America’s patients from benefiting from the cost savings generated by generics and biosimilars products.

Exhibit 1. IRA Timeline Problems with Respect to Generic Drugs, Indicates Years Since Reference Product Approval

Exhibit 2. IRA Timeline Problems with Respect to Biosimilars, Indicates Years Since Reference Product’s Approval

References

- Note: fluticasone/umeclidinium/vilanterol and fluticasone/vilanterol do not have any known approved, pending, or tentatively approved ANDAs. To determine the number of approved ANDAs, tentatively approved ANDAs, and pending ANDAs, consultants reviewed various source documents, including court documents, Drugs@FDA, etc. to determine the specific ANDA numbers and status for each molecule. Pending ANDAs are ANDAs that have been filed, but the FDA has not yet opined upon them. AAM acknowledges that not all pending ANDAs will be approved. Holders of tentatively approved ANDAs (when the ANDA meets the substantive requirements for approval but cannot receive final approval due to patent or exclusivity reasons) must notify the FDA when the patent/exclusivity issues have been resolved to obtain final approval. Many of the approved ANDAs have resolved their patent litigation, but the resultant effect is that the product is prohibited from immediate launch.

- Amgen launched the product “at risk” before the close of patent litigation.

- FDA. Generic Competition and Drug Prices: New Evidence Linking Greater Generic Competition and Lower Generic Drug Prices. December 2019. Here.

- AAM further notes that CMS’ distinction between biosimilars and interchangeable biosimilars is contrary to policy positions outlined by the FDA, in which FDA has advocated for all biosimilars to be deemed interchangeable, as outlined in a recent JAMA article. (Here)